As a bilingual speech-language pathologist, I am honored to serve culturally and linguistically diverse families daily. Through my education and experiences, I have learned so much about bilingualism and the importance of celebrating all languages around the world.

Nearly 25% of public school students now speak a language other than English at home across the U.S. Of these children, 85% were born in the United States. In Texas, almost 33% of school-age children speak another language at home and that number is projected to continued growing (Center for Immigration Studies, 2018).

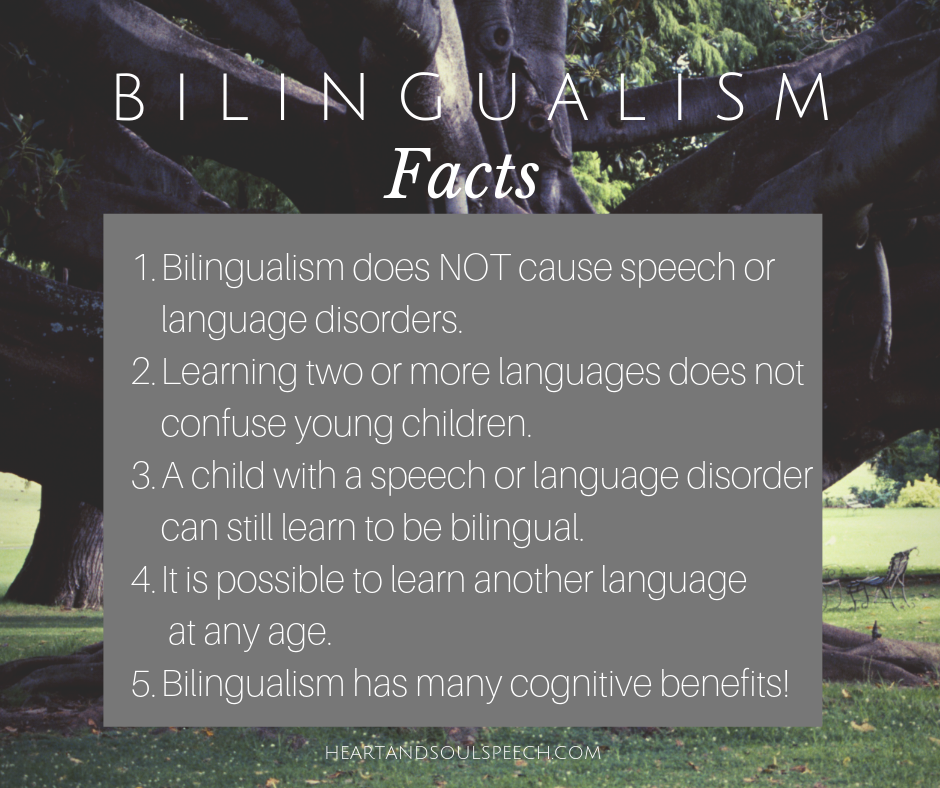

When it comes to bilingual language learners and speech disorders, I hear so many misconceptions. Here’s the FACTS you should know about language development and bilingualism!

1. Exposing infants and toddlers to more than one language DOES NOT cause delays in the speech or language development.

“A disorder in bilinguals is not caused by bilingualism or cured by monolingualism.” (Kohnert, 2008)

If a child has a true language disorder, it will be present in BOTH languages. If a child only shows difficulty in one language, then it is a sign of emerging language and called a “language difference.”

Language Disorder(would likely benefit from intervention) |

Language Difference(does not need intervention) |

Difficulties with:

|

Difficulties with:

|

Children learning more than one language will speak their first words around age one and be able to combine two-word phrases by age two. This is the same expectation for children learning only one language. A bilingual toddler may “code switch” or mix parts of a word/sentence from one language with parts from another language. This is a normal part of bilingual language learning. The total number of words a child uses from both languages should be within the same range as monolingual children.

Vocabulary Norms

| Age | Bilingual Children

(two+ languages) |

Monolingual Children

(one language) |

Red flags |

| 12 months | 2-6 words (total words added from all languages)

Example: mamá, papá, perro, cat, milk |

2-6 words

Example: momma, dada, woof, cat, milk |

No babbling, not trying to say adult-like words |

| 15 months | 10-25 words | 10-25 words | Fewer than 10 words (from all languages combined) |

| 18 months | 50 words | 50 words | Fewer than 20 words (from all languages combined) |

| 24 months | 200-300 words + combining two words together

Example: Más milk |

200-300 words + combining two words together

Example: More milk |

Fewer than 50 words and not putting two words together |

2. Learning two or more languages will NOT confuse your young child.

As young children learn more than one language, they may mix up grammar rules or use words from both languages (“code switch”). Again, this is normal for bilingual language development. Usually by age 4, a bilingual child will be understood by other bilingual speakers. A monolingual child is also expected to be understood almost all of the time by age 4.

Simultaneous Bilingual learning = a child begins developing two languages before the age of three years

Phases of development:

- Bilingual child uses one language system with words from both languages.

- Child will use mixed language (“code switching”).

- Child will use two separate grammar rules to distinguish the two languages.

- Use of either language will depend on the environment

Sequential Bilingual learning = a child begins developing a second language after three years of age

Phases of development:

- Child learns native language with grammar rules and vocabulary.

- Child is exposed to new second language with different grammar rules and vocabulary.

- Silent Period – Child listens and learns new language without much attempt to practice using the language. This may last 3-6 months.

- Language Loss – As the child acquires the second language, child may lose language skills previously used in native first language.

- Language Transfer – Child begins to use grammar rules from first language when speaking in second language.

- Codeswitching – Child mixes languages and rules between the two languages.

- Child will understand two separate grammar rules to distinguish the two languages.

- Use of either language will depend on the environment.

3. A child with a speech or language disorder CAN continue to learn a second language.

If your child shows a language disorder in both languages, that does not mean you need to only teach one language. Research shows with intervention, a child can successfully use more than one language.

**If you have concerns about your bilingual child’s language development, please seek out a speech-language pathologist with bilingual experience.**

Caregivers of both bilingual and monolingual children can ask themselves the following questions to determine if there may be a language disorder or delay present:

–Is my child’s speech clear?

–Does my child make friends easily?

–Is my child comfortable communicating with friends and family?

–Can my child communicate independently?

–How often do I understand my child?

–Does my child use more gestures than words?

4. It IS possible to become fluent in more than one language at any age.

Research supports language-learning happens most rapidly during the first years of brain development; however older children and adults can become fluent later in life with practice.

5. Bilingualism has cognitive benefits!

Research shows people who are bilingual use more parts of their brain during communication than those who only speak one language (Marian & Spivey, 2003), and that the brain structure itself actually changes to allow for language switching (Mohades, et al, 2012). The bilingual brain depends on executive function, the area of the brain that controls our impulse, morals, decision-making, attention, etc. (Bialystok, Craik, & Luk, 2012).

Resources:

- International Expert Panel on Multilingual Children’s Speech

- Multicultural issues and resources

- Healthy Children.org

References:

Bialystok E, Craik FI, Luk G. Bilingualism: Consequences for mind and brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2012;16(4):240–250.

Center for Immigration Studies, 2018

Kohnert, K., Windsor, J., & Ebert, K. D. (2009). Primary or “specific” language impairment and children learning a second language. Brain and language, 109(2-3), 101–111. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2008.01.009

Marian V, Spivey M. Bilingual and monolingual processing of competing lexical items. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2003;24(2):173–193.

Mohades SG, Struys E, Van Schuerbeek P, Mondt K, Van De Craen P, Luypaert R. DTI reveals structural differences in white matter tracts between bilingual and monolingual children. Brain Research. 2012;1435(72):80.

One Response