If you’re looking for ways to help your child talk, you’re in the right place!

Please note: This article and it’s content, including linked articles, is for educational purposes and is NOT a replacement for intervention from a licensed speech-language pathologist (SLP) or professional medical advice. If you are concerned with your child’s speech and language development, please find an SLP in your area.

We whole-heartedly believe (and research supports, too!) that caregivers can be just as effective as speech-language pathologists when using the right strategies! No one can make your child talk, but we can help children learn to use words and build language using these tips. All children learn from watching others, but children who are “late talkers” or have language delays/disorders need even more support. Sometimes that means we must change the way we model language for the child to learn. We can respond differently and change the environment to promote language in their lives. You are their best teacher!

If you have concerns about late talking, please talk with your pediatrician and request a hearing screening to rule out hearing loss.

STEP ONE: Answers to Common Questions

Before skipping ahead to the strategies, check out these articles to find answers to common questions about speech and language development.

Speech & Language: What parents need to know

STEP TWO: Zone of Proximal Development

Not all strategies work for all children. It’s important to know where your child is before raising our expectations. The Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) is the difference between what a learner can do without help and what he can do with help. (This concept was developed by psychologist Lev Vygotsky; you can read more here.)

Think of Goldilocks and the three bears – We want to use strategies that are not too hard and not too easy, but just right for their skills. In other terms, we want to support the child where she is and then challenge her just enough to build her language in small steps. We do not expect a child who only uses grunts and eye contact to immediately start using words. We need comprehension, imitation, attention and interest, and functional sounds first! Not every strategy may be a good fit for your child; consulting with a speech-language pathologist is best practice if you have concerns.

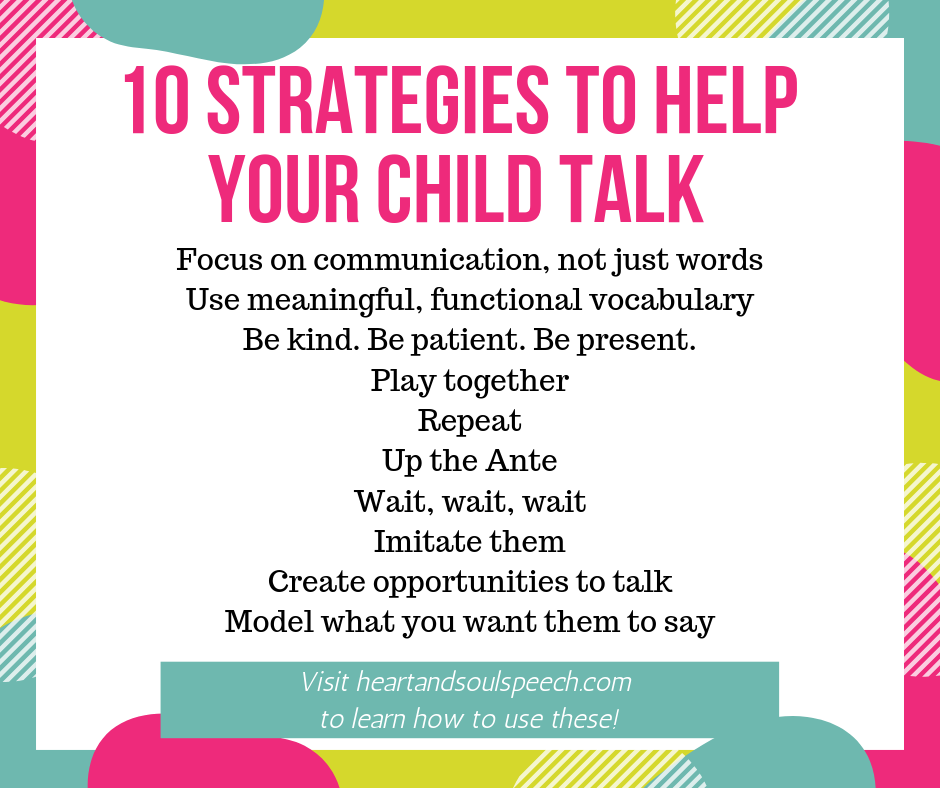

STEP THREE: 10 Strategies we Love to Help Children Talk

Finally – Let’s learn 10 strategies to help your child talk!

-

Focus on communication, not just words

I know – words are the goal. However, sometimes we can get so wrapped up about trying to talk, that we forget where the child is right now (read ZPD above). We want to create opportunities for children to communicate, not test them on what they don’t know. Trust me, if a child could talk, they probably would.

Often, caregivers try to teach language by asking “what’s this? or “say X.” The child may (or may not know) what it is, but does not have the ability to use a word to label it yet. This results in frustration for everyone. If the child is unable to imitate words, perhaps try simple signs or gestures to support the child. Once they are able to show you what they mean, then we can target words.

Another way to support language without “testing” is to turn your questions into statements.

| Instead of this… | Say that! |

| “What’s that?” | “Oh you have a ball! Bounce, bounce, bounce!” |

| “What’s that?” | “A shoe? A carrot? OH, of course, it’s a dog!(the sillier, the better) |

| “Where’s he going?” | “I wonder where he’s going? Vroom!” |

-

Target meaningful and functional words during everyday routines.

Each child will have words that are more important than others depending on their daily routine. This often means we can target vocabulary just by thinking about their everyday life. Think of their favorites: people, toys, foods, things to do. Those are the focus words. Model and highlight what you’re doing as you do it!

Early talkers often have many nouns, but are missing other important words like action verbs, pronouns, and descriptive words. Counting, shapes, and letters are not very meaningful (unless your child is really into it) in the beginning. There are likely many more meaningful words that need to come first! Check out this list of functional vocabulary by Laura Mize.

-

Be kind, be patient, be present

It can be scary and frustrating to not be able to express yourself in a way others understand. Have you ever traveled to a place that speaks a different language? Ever been unsuccessful in getting your point across, no matter what you try? What about leaving a conversation feeling like you weren’t truly heard?

Our children with language delays may feel this way often. Caregivers who are intentional about showing patience and kindness when our children attempt to communicate support language growth. We can offer two choices when we recognize our child is struggling to use a word. When they point to something, give them the word of what they want before you ask a question, and then model what they should say. “Milk. Do you want milk? Yes, I want milk!” When they grab your hand and pull you toward the unopened playdough, model again what they should say. “Playdough. I need help. Open please.” Connect with your child during the day so they learn what they have to say is important.

-

Play together! (Follow their lead)

Play is so important for our children’s development and that includes language! Read our play series to learn more!

-

Repeat, repeat, repeat

Repetition can get tiresome for adults – sometimes my whole therapy session only consists of 5 words that I use over and over, and over again. The toy cars drive up and down the hall. The bubbles fly up and down. After that, the child jumps – you guessed it – up and down. By the end of the session, I’m worn out. But you know what? The child had a blast and now has a deeper understanding and ability to use that vocabulary!

Research indicates a child may have to hear, see, and use a new word 15-20 times before they truly learn it. Children with language delays may have to be exposed up to 40+ times before they learn it. The pathway in the brain has to be built. The new word has to be connected to what they already know, organized and filed away by category or pattern, and then be able to pull it out again later. Children begin to experiment with the word, using it in different situations until they learn and use it correctly. Keep repeating, my friends!

Read more about vocabulary and how children learn new words through repetition.

-

“Up the Ante”

This also goes back to the ZPD and where your child is at in the moment. We continuously want to increase our expectations within reason, challenging the child to do more in a supportive environment. We can encourage them to be successful where they are and then “up the ante” to teach them new skills. How we raise our expectations depends on the child, but with consistency and recognition we can slowly make changes to build language.

Let’s look at how we can “up the ante” with Molly:

Molly usually cries when she wants a new toy. Mom tries to guess by asking “Do you want the baby doll?” Molly cries harder. Mom asks “Do you want the blocks?” Molly grabs the blocks and stops crying. Mom lets her have all the blocks and watches her play quietly.

(The expectation here is low. Molly just has to cry and wait for mom to guess what she wants before she gets it.)

- Molly cries for a new toy. Mom offers Molly blocks and baby dolls. Molly goes to grab the blocks without making a sound or even eye contact. Mom says, “Oh, you want the blocks! Let’s sign ‘give me’ so I understand.” Mom helps Molly sign ‘give me’ and then gets two blocks.

(We’ve now raised the bar by asking Molly to gesture to request what she wants. Mom immediately reinforces her attempt to gesture and she successfully gets what she wants.)

2. Molly cries for more blocks, but eventually puts her hand out to gesture “give me” after Mom waits a few seconds. Mom immediately gives her two more blocks and models “More blocks!”

(Molly is now learning crying isn’t working anymore, but if she puts her hand out to request more, she gets it!)

3. Molly begins to put her hand out to sign “give me” more consistently and Mom reinforces it while always modeling “More blocks!” Now, Mom raises her expectations for Molly to imitate her by making a “m” sound to request “more” before giving more blocks. “You want more blocks! Let’s say ‘mmmore’ so I understand.” Molly may continue to put her hand out to sign, or even go back to crying. However, Mom’s consistent expectation for Molly to make a sound (any sound at first) and immediate reward of a block will help Molly continue building on her language skills.

-

WAIT. WAIT. WAIT.

This can be another hard one for caregivers. Our world is so quick and we are used to keeping up. However, for the children learning language, they need time. They need us to wait.

I once had the honor of hearing a little guy’s first word using this strategy with mom while racing cars. Mom and I modeled “Ready, Set….GO!” probably a million times in the session, increasing our wait time each time before we said “go” and made the car race down the track. He was so engaged in the race, but would never say “go!” In the last few minutes of the session, I decided to watch the clock and give him 30 seconds before the cars moved. He locked eyes with Mom, waiting for the race. Mom said “Ready, Set…” and we waited. She “revved her engine” a few times, but still did not move. At 23 seconds, that little boy yelled “GOOOOOOOOO!!!!” and raced his car to the finish line while Mom and I cried tears of happiness.

Ever since then, I wait.

-

Imitate them, so they will imitate you.

Learning to imitate is essential to learning to talk. We learn new skills by watching others and trying to do the same. This can start with young babies. We copy their actions first, then sounds. When they drop the toy, you drop the toy. When they laugh, you laugh. We copy their actions and they become more engaged. Then, we put words to the action and there’s a magical language opportunity.

Children need to be interested in order to imitate us. They often don’t think our fun is fun. Children probably won’t copy saying “shoe” for the first time when we model putting away their shoes. However, they may say “shoe” when pulling on your shoestrings.

-

Create opportunities to talk

For our language learners, we need to enrich the environment with opportunities to talk. In the SLP world, we sometimes call this sabotage. Maybe it sounds a little mean, but really it’s just pretending to be forgetful!

Sometimes we need to set up their world so they need to ask for your help. We can’t just do it for them, but need to let them learn to use their words to be successful. Even better, when we pretend to forget something, it can help children feel like they are helping US. They can problem-solve with us and have an opportunity to communicate. You’ll likely be surprised at just how much they know!

Examples of being “forgetful:”

- Put their favorite toy out of reach, but in sight.

- Give them the playdough with the lid still on.

- Offer them their cup without any water inside.

- Give them only one shoe.

- Keep the last puzzle piece.

-

Model what you want them to say.

Caregivers modeling language often sound like sports broadcasters. They narrate or comment on everything they see happening. Modeling is speaking your child’s unspoken thoughts. Try following the child’s play, even if it isn’t obvious what your child is thinking. Describe what your child is doing, instead of what you want him to do.

- Zach quietly covers the teddy bear with a blanket. Dad watches and then models out loud, “Teddy is tired. It’s time for bed! Shhh!” (That’s probably what Zach is thinking, but isn’t able to say yet. Dad puts the words to Zach’s thoughts.)

- Sam bangs the puzzle pieces on the puzzle board, but doesn’t put them in their spot. Dad starts to help make the pieces fit, but observes and realizes Sam likes the sound it makes. Dad models “That’s a loud sound! Bang Bang!” (Great job following Sam’s lead, Dad!)

Again, if you have concerns about your child’s speech or language development, please seek a speech-language pathologist.

8 Responses